- Home

- Chris Bauer

Hiding Among the Dead

Hiding Among the Dead Read online

Hiding Among the Dead

Chris Bauer

Copyright © 2019 by Chris Bauer.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Published by Severn River Publishing.

Contents

Also by Chris Bauer

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Also by Chris Bauer

Thanks for Reading

Scars on the Face of God

SCARS ON THE FACE OF GOD: Prologue

SCARS ON THE FACE OF GOD: Chapter 1

SCARS ON THE FACE OF GOD: Chapter 2

Read Scars on the Face of God

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Chris Bauer

Scars on the Face of God

Hiding Among the Dead

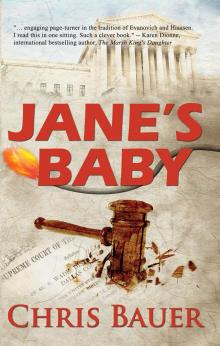

Jane’s Baby

Sign up to get exclusive access to updates, special offers, free books and new releases from Chris Bauer and the SRP Mystery & Thriller Team. ChrisBauerAuthor.com/Newsletter

To grandson Evan and granddaughter Teddy. Dream big then go bigger. So proud of you already.

1

The stink from the river was badass intense, dizzying, even in the cold air, like rotting meat from a dead animal, odor as oppressive as wind resistance. It clung to them while their step van drove south on the Schuylkill Expressway. Why Grace felt she needed to comment on it considering their line of work, Philo didn’t know. While he drove, she replaced the dead air with small talk.

“From skunk cabbage. They planted it up and down the Schuylkill River maybe fifteen years ago. It reduces sewer system overflow into the river during rainstorms. The smell sometimes finds its way here.”

Maybe, just maybe, she’d stop there. Grace was never more than a thought away from going drunken-sailor nuclear. An overnight phone message put them on the road today. That and the slur recorded with it, from an Amtrak cop barking at a subordinate to better the din of an arriving ambulance on his end: “I don’t give a shit who else is coming. I want the Gore Whore here too…Oh, hello, Grace. Amtrak Police. Multiple fatalities near Zoo Junction. Call me ASAP at two-six-seven…”

Every law enforcement agency in Philly knew Grace Blessid as the Gore Whore. The slur got them jobs, so the tough white Germantown woman didn’t discourage it. It made sense: she had a nasty mouth, she toiled in a gory environment, and she’d acquired law enforcement contacts from a rumored prior career on the streets—and it rhymed. Philo had heard things far worse about female peers while in the navy, but rarely had these things come out of their own mouths.

Philo learned all this soon after he bought Blessid Trauma Services, the crime scene cleaning business Grace and her husband, Hank, had built from scratch. Grace Blessid was sick; she needed new lungs, like, now. After thirty-four years in operation the business traded hands, with Tristan Trout, “Philo” for reasons he hadn’t shared, now the new owner.

“Smells bad as an unwashed cunt, doesn’t it?” Grace said.

And she was Catholic.

“Really, Grace?” Philo said. “That’s the image you’re going for?”

“Tell me you weren’t thinking it.”

“You’re killing me, Grace.”

Grace, late fifties, kept her auburn hair under a large, tied-off silk scarf, today’s colors Philadelphia Flyers orange and black, one end pulled forward to lay flat like a koi fishtail across cream-white cleavage her blue uniform didn’t hide. At one time she’d been smokin’ hot, her words. Now she was a little bit less so, with clear cannula tubing leading from her nostrils to the portable oxygen concentrator stuffed into the backpack at her feet. For the next four months, per the agreement of sale, she was Philo’s on-the-job trainer, one of two. The other was Hank, her husband, his bulk currently planted in one of the two jump seats behind them, his earbuds plugged into Zeppelin.

They neared their destination, the expressway’s Philadelphia Zoo exit. A second biohazard cleaning service had been at the site all night.

Philo was fifteen years absent his northeast Philly roots, and at thirty-nine was bruised from his military deployments but still looked cowboy lean and mean. He’d decided to return home, to blend in as a citizen. When he found a business suited to his proclivities and his disposition, he assembled the financing for it.

“Let there be no illusions, Mr. Trout,” Grace said when they first met over drinks, leaning into her rheumy-eyed stare. “These chemicals will severely limit your life expectancy if you don’t pay attention. Sad thing is, I can’t sue myself. ’Course, I also liked my unfiltered Camels, so that didn’t help.” Grace couldn’t still be a smoker and stay on a transplant list, which meant she fought her craving every day. “I’m cooperating, maintaining this charade, for my husband. He’s not taking this terminal illness shit very well.”

The business ran fine with three employees—Grace, Hank, and their protégé, Patrick—and would do so with the same number after the transition, meaning Hank, Patrick, and Philo. That is if Patrick, damaged goods in his own right, stayed stimulated and entertained, and if Hank wanted to stay on board. Grace’s medical condition had turned Hank into a weepy sieve.

Belted in stiff as a storm trooper, young Patrick sat across from Hank in the step van, plugged into 50 Cent, his blue Tyvek biohazard suit the heaviest of heavy-duty over his uniform, his mask in place, too. Grace spoke over her shoulder, raised her voice.

“Warm in that suit, Patrick?” she asked, winking at Philo. They knew it was, even though the cold outside was brutal.

Patrick removed an earbud. “Only a little, ma’am.” Standard answer, winter, summer, ice age, heat wave. He was a traumatic brain injury victim from an event that took his real identity and left behind the adult equivalent of a five-ten mound of Silly Putty. The hospital’s neurological assessment: dissociative amnesia. Per the caseworker’s notes: “Found with no vitals a block from Pat’s King of Steaks restaurant on Passyunk Avenue by Pat’s employees, February 15, 2014. In a coma for four days. He doesn’t know his name or age. Could barely speak when he returned to consciousness.”

Best guess was he was now midtwenties. Survived a bludgeoning, was left naked inside an open dumpster a few days after a blizzard dropped ten inches of snow. The trauma preceded his life with the Blessids, which meant it was more than three years ago. Patrick came with the business; no Patrick, no sale. What the trauma hadn’t stolen from him, and what its aftermath couldn’t hide, was his ethnicity. He was an Eskimo, or at least everyone thought he was. Philo had traveled the worl

d during his military deployments, but Patrick was the first Eskimo he’d ever met.

“Aleut or Inuit,” Grace said, correcting Philo back then. “Or so thought Catholic Charities. They said Eskimo as a word is pejorative, so we don’t use it. No idea how he ended up in Philly. A tourist visit gone wrong, teleportation, who the fuck knows. ‘Patrick,’ from Pat’s Steaks, near where he was found, was as good a name as any.”

The end of Patrick’s fifth day after his discovery, he disappeared from his bed at Pennsylvania Hospital. No one came looking for him, before or after.

A cold snap today, twenty-eight degrees would be the high, and this kept Patrick from oozing sauna-grade sweat inside his suit during their ride; Tyvek biohazard suits didn’t breathe. At attention in his seat, he was the epitome of preparedness and concentration, ready for the job every time he left his apartment above the Blessids’ detached garage. He removed his mask, sipped water from a bottle.

Grace’s husband Hank removed his earbuds. “Today’s job is hunt and gather, son,” he said to Patrick. The Blessids had no children. They saw this man-child as son and grandson wrapped into one.

“Hunt and gather,” Patrick repeated. “Then clean.”

“Yes, son, there’s always cleaning.”

“Here’s our exit, Philo,” Grace said.

Their black 1998 Freightliner step van, boxy with a head-turning custom paint job, left the expressway and entered street traffic. On the truck’s side panels and rear door were waist-up photorealistic images of the three Catholic popes who’d held the title since the Blessids opened their business in 1983. John Paul II and Benedict XVI were in their papal whites, as was Francis, a 2013 addition, each with their right hands raised chest high and poised to deliver sign-of-the-cross blessings to motorists as they sped by. The step van stopped at a red traffic light. A Ford SUV pulled alongside in the left lane.

The SUV’s passenger window powered down while the vehicles waited for the light to change, releasing a most righteous ganja haze. A giddy teenager smiled up at Philo through it, struggling with loosening the belt holding up his pants. The stoner shimmied his pants down to his knees and presented two ass cheeks for close papal inspection through the open window—“Bio-clean this hazard, Pope-dudes!”—then dropped back into his seat in hysterics.

It wasn’t like Philo was still a practicing Catholic, but no one got away with mooning the Pope.

Philo slid aside his window and summoned a serious scowl beneath his unruly brown hair, a rooster comb separating a dually receding hairline. He grabbed a stray rubber glove from the dashboard ledge and tossed it into the kid’s open window, the glove landing in his exposed lap. “Enjoy the rash, kid.”

It wasn’t contaminated, but hell, the kid didn’t know that. The traffic light changed, Philo turned right, then found off-street parking near the zoo.

A call to the Amtrak police got them onto the tracks. Their contract with Amtrak was a two-year deal carved up among multiple biohazard vendors along the railroad’s Northeast Corridor, the route that ran from Boston to DC. Still cold, still cloudy, an icy breeze buffeted their faces as they walked, the four of them in blue Tyvek with goggles and headlamps at the ready above their foreheads, and filtered respirator masks hanging loose around their necks.

The train’s eight cars—two power cars, six passenger—sat large and ominous ahead of them on the track, just past the curve and near the zoo entrance. Philo’s eyes gravitated to the lower third of the silver-and-blue power car. Below the engine’s red line, the wheels and undercarriage were caked black and gray with dirt, grease, and track grime—plus, hopefully, a certain something that a certain grieving family prayed they could recover.

This was yesterday’s five p.m. 2167 Acela Express out of New York’s Penn Station, which had motored through the slight curve around the zoo at eighty miles per hour until just before impact. Per the engineer’s statement he saw three people on the tracks, a woman and two young children holding balloons, all holding hands. He sounded the horn and applied the brakes, which had no chance of stopping the train until well beyond the collision point. Closer in, the engineer saw the woman better—young, brown-skinned—and also saw a baby sling snugged up against her chest. She dropped down and lay across the tracks with the small children, their three helium balloons hovering. The victims disappeared in the undercarriage; the train did not derail.

Moving at the speed of Grace, her portable oxygen in her backpack, she and Hank trailed Philo along a paved walkway, and Patrick trailed them all, pulling a stubby all-terrain cart with pneumatic tires. Patrick eased the cart off the paved walk onto the tracks’ stone ballast. The cart was stuffed with cleaning equipment, red hazmat bags, a short stack of empty twenty-gallon biohazard containment drums, solvents, gloves, soft brushes, wire brushes, tape, and tools. Tucked into a plastic bag somewhere was a large jar of Tiger Balm, which Grace swore by for smell management. An Amtrak maintenance supervisor trotted up to them.

“Who’s in charge here?”

Philo gave Grace a questioning look; she nodded him an okay. “That would be me,” Philo said, and introduced himself.

“Okay then. So Mr. Trout, let’s go over a few things. You’ll need to be thorough but quick. Service has been moved to another track, but the muckety-mucks want service restored to this one ASAP. Another biohazard company will work from the other end of the train as soon as they finish policing the tracks. I understand a spokesman from the woman’s family called you guys. If you can do what they asked, we’ll cooperate. Any questions?”

The local detectives cleared the scene as non-investigative. Showtime for Blessid Trauma.

“Patrick, you and I are going underneath. We’ll shimmy from the power car back. Hank, lay the tarps over there for our biohazard control area. You and Grace can follow alongside us with the cart. Patrick, switch on your headlamp and get your phone camera ready.”

Patrick fished his mobile phone out of a pocket, held it up, took a selfie, and showed it to Philo.

“You are one ugly dude, Patrick. Lock and load, buddy.” Philo patted Patrick on the shoulder. “Cleansing breath, game face on. Let’s go get dirty. And remember—no one better than you, Patrick.”

“Sir! No one better than Patrick, sir! No one better than Patrick, SIR!”

For Patrick, the switch had been thrown. For Philo the chant was a mixed bag, recalling long, maddening daily marches from a once very serious, very disciplined, and very dangerous past.

They lay down on the stone ballast, Patrick softly repeating the mantra, keeping himself fired up, about to crawl into the belly of the beast. He lifted his breather mask in place over his nose and mouth, relegating his chant to humming and grunting. They shimmied underneath, dragging their bag of tools with them, he and Philo shoulder to shoulder.

Clearance under the nose of the train was minimal, the edge of the power car’s front baffle scraping their chests as they wiggled past it, their headlamps on. They inched forward, their shoulders pushing against the rough-cut ballast under them. Polyethylene-coated coveralls and their uniform pants and shirts were heavy enough to protect them from puncture, but not heavy enough to soften the prickling discomfort.

The way Philo saw it there were three good things about this removal. One, it was outside, not in a confined, under-ventilated area like most of their jobs. Two, the weather was cooperating, with the frigid air limiting the immediate area to the more palatable smells of creosoted rail ties, grease and oil, and hints, mild only, of rat scat. Three, most of the heavy lifting from the four fatalities had been handled already. Forensics personnel, firemen, and the other crime scene cleaners had policed a stretch of track a full hundred yards beyond where the last few body parts were found. Whatever was left would be crammed into, hanging off, or maybe now frozen against the undercarriage of the eight-car train.

Which brought Philo to the one bad thing: the grieving Hispanic family, last name Marroquin. The info Amtrak had from a family relative was the youn

g woman had recently lost her husband. The family’s request was to locate a body part still missing, and to retrieve it as reverently and as carefully as possible; either that or confirm it wasn’t there. In preparation, Philo supplemented his tool bag of normally less discriminating putty knives, tongs, chisels, and scrapers with two new instruments: a surgical scalpel and a bone saw.

Their order of work: take “before” photos; inspect each linear foot, wipe away blood and other body effluence, and carefully scrape off anything resembling a human body part and place it in a hazmat bag; clean with crud-removing, disinfecting solvent; take “after” photos; then shimmy forward another foot and repeat the process.

The undercarriage of the first power car contained, in no particular order, metal baffling, axles, steel wheels with wheel grease, traction motors, springs, tubing, large nuts and bolts, steel plating, and a myriad of other filthy surfaces. Their first discovery, inside a coiled spring, was a section of intestine glistening from crystallized internal moisture. Philo removed it with needle-nose pliers and tweezers and placed the pieces inside a red hazmat bag. After that, the hits kept coming. Lodged under an interior baffle was a severed child’s foot in a no-name athletic shoe, and the back of a child’s hand including knuckles and one hanging finger, the nail painted fluorescent lime. A popped Mylar balloon hung flaccid from an axle, the words on the balloon in Spanish and the string still attached. Tangled in the string, a baby’s pacifier. And a ragged chunk of adult ass in jeans twisted around a steel tie rod, the butt crack the giveaway, already frozen in place by the extreme overnight temperatures. Philo used a pry bar to free the frozen ass-flesh from the frigid metal, needing to put his weight into it and ripping off a pocket on the jeans in the process, which liberated a piece of folded paper. He dropped his gloved hand on it before the icy wind could whip it away.

Zero Island (Blessid Trauma Crime Scene Cleaners Book 2)

Zero Island (Blessid Trauma Crime Scene Cleaners Book 2) Scars on the Face of God

Scars on the Face of God Binge Killer

Binge Killer Hiding Among the Dead

Hiding Among the Dead Jane's Baby

Jane's Baby