- Home

- Chris Bauer

Hiding Among the Dead Page 3

Hiding Among the Dead Read online

Page 3

“Ambulance companies chasing people who aren’t quite dead yet, Philo. That’s who he works for.”

“Isn’t that the whole ambulance idea?”

She ignored the comment. “Some of their patients make it, some don’t. Some of the EMTs contact that Frankenstein prick Andelmo to let him know what’s coming in, then maybe even dial down their service a little to hasten the inevitable. A for-profit transplant specialist. Andelmo’s the ringleader.”

One thing that was true about this surgeon, who was affiliated with a few Philadelphia hospitals, was he was in a ton of trouble, with the press already convicting him in the court of public opinion. Made public were a number of malpractice lawsuits; patients getting routine procedures who had died on his table. For one, an appendectomy, for another, a gallbladder—both patients, coincidentally, organ and tissue donors. Andelmo had questionable associations with influential people in need of all sorts of transplants—wealthy people and celebrities—who suddenly got them. All of it remained innuendo until a criminal case could be made. Something the Philadelphia DA was apparently pursuing.

“Lose the ‘Frankenstein’ BS, Grace,” Philo said. “It stopped being funny after the first ten times I heard it.”

Hank, from the back seat: “What Philo said, honey. Give it a rest, please.”

Grace narrowed her eyes at her husband, then she caved. “Only because you said please, doll.”

Dr. Francisco X. Andelmo, Grace’s “zombie” doc, was a neurological surgeon in his early fifties, with positions in two Philadelphia hospitals plus other hospital relationships south of the border. That was the extent of what Philo knew about him. Good guy, bad guy, Philo didn’t know, didn’t care, and had no reason to think he ever would. But to Grace he was the antichrist.

Philo put up with Grace’s conservative rants from the beginning, and he wouldn’t stop now. She’d been a good sport about playing through her disease, a hardship factor that upped her standing in his eyes a thousandfold. Plus, she, too, was on one of those transplant lists the celebrities and wealthy people seemed to bypass, so it wasn’t like she didn’t know what she was talking about. But her “in general, if it walks like a duck rants” and her in-particular attitude toward government overreach, had begun to grate on him.

Philo balled up his sloppy sandwich wrapper and found an empty paper bag for it. “You check the messaging service to see what else we’ve got for today, Grace?”

“A Philly cop car. It’s in this neighborhood, three blocks up. A perp accident, in the perp seat.” She tucked her Camel away into a blouse pocket, watched outside as Patrick took his Pat’s Steaks buddies through some well-executed, straight-outta-Compton special goodbye handshakes.

Red flag language for Philo: perp mess in a cop car. Police lawsuits had surfaced around the country, cops suing their cities for having contracted hepatitis and HIV from contaminated crime scenes. One outcome of the legal actions was increased work for the crime-scene cleaning industry, cops not wanting to contract diseases, cities not wanting to settle lawsuits if they did.

“Grace, if this is a few cops tuning up a perp, call them the hell back and tell them to clean up their own mess.”

“Relax. The guy threw a tantrum in the back seat, took a dump, horked up his lunch, then pounded his head against the glass. PCP, maybe meth, bath salts, maybe all of it, the cops weren’t sure.”

Her fingers returned to her blouse pocket, retrieved the Camel she’d given up a minute earlier. She reinserted it into her mouth and went through the motions again. “You need to cut the cops some slack, Philo, the crap they put up with. Hank, honey”—she reached back, tapped her husband on his knee—“this squad-car thing, you and I are up. Would you mind handling it for me, doll? I’m just not in the mood.”

Hank leaned in next to her in her seat, concerned. “Grace, honey, you think maybe you should—”

“I need to just not do this next job is all I need to do, sweetie, so relax.” She cupped his cheek. His eyes welled; she swiped at a tear with her thumb. “Just not feeling it now. I’ll be fine, love, just…It’ll all be fine.”

Two minutes down Passyunk, then a left onto Washington. Philo parked in front of the cop car, an unmarked Chevy Impala, a detective’s car, so he felt better about it. Less chance there’d been any funny business in the back seat. The rear doors were ajar, and they could see some of the perp’s brown and pinkish redecoration efforts caked onto an inside door panel.

Philo and Grace answered texts, and Patrick stayed connected to an online game app. Hank worked the job, the blood, the feces, and the puke all as promised, and no doubt sweat and tears also, but it was all apparently perp-initiated. Except for the tears part, where a depressed Hank, working alone, was also a contributor.

3

Kaipo Mawpaw lifted the cha siu bao with her chopsticks, admiring its dense texture. Stuffed inside the soft bread-bun was diced barbecued pork tenderloin mixed with Cantonese sauces, the last dim sum of her five-course meal. On Oahu this dish was called manapua, which meant “delicious pork thing.” Kaipo took a tentative, inquisitive bite, then she took a less dainty bite to finish it. She devoured the second bun with gusto. She placed her chopsticks on the table, poured herself more tea.

The Happy Empress Cantonese Restaurant dining room was tiny, only seven café tables, each decorated with a wine-red tablecloth, a burning yellow candle, and two white cloth napkins, but its take-out business was robust. The stream of customers was constant, passing behind the drapes that hid the glassed-in hallway.

Tonight she was one of only two dining room patrons. At a second table an elderly Asian man tossed toothless smiles and furtive glances her way between slurps of soup and hearty bites into large, meat-filled dumplings, the food no match for his hardened gums. The smile was respectful, not leering—she knew the difference—and wasn’t meant to elicit conversation, was offered instead only in reverence to her wholesome, natural Polynesian beauty. For Kaipo this was refreshing, and so dissimilar to the usual reception she got whenever she met friends for drinks, from trolling men or curious women, all looking for a change in their partners short-term, to someone a bit more…formidable. Kaipo oozed femininity yet was not a shrinking violet. At five ten, her well-proportioned femininity was far from a shrinking anything.

The male waiter delivered the check then bowed once before retreating to the kitchen. No charge, with our compliments, it read at bottom, which was how all her checks read at this restaurant for the few years she’d frequented it, coincident with the same number of years she’d spent on the mainland. The free meals were not a privilege she abused. She ate here only once a week, on Thursdays, the day her clandestine employer had requested. It was a visit that meant, on occasion, a few subsequent days and nights would be busy, with her doing what they wanted her to do and getting paid handsomely to do it. With her dinner check came a handful of after-dinner peppermints and one very special fortune cookie. Dipped in chocolate and absent any cellophane, she would enjoy the fortune cookie dessert first.

She pushed her hair back over her shoulder, cracked the cookie open with a fork, the milk-chocolate encasing it not fully hardened. When she pulled it apart, the soft chocolate made the pieces stringy, like chocolate saltwater taffy; the dessert couldn’t be any fresher than this. Inside, the tan strip of paper bore her fortune. She lifted it to her nose to savor its fragrance, strawberry, its lettering red and glistening, further enhancing the aroma. She flattened it against the tablecloth to view the message.

The words on the small strip were in cursive, handwritten with decent penmanship. She read the instructions, then she fed the paper into her mouth and ate it, too. Its wafered texture was sweet and fruity and as edible as the scent suggested.

She raised her attention from the dessert plate. The old Asian man had put aside the ripped cellophane from a standard pre-packaged fortune cookie that accompanied his dinner, his gaze now moving from her empty plate to her hands to her face, his gumming of hi

s cookie slow, ponderous. To her, his apprehension looked like fear, and this fear might mean he knew something about her, her connections, maybe her avocation. Or somehow maybe he knew the instructions that were in her fortune cookie. To her, he was suddenly now, sadly, a danger.

She told herself he was old and his life was behind him, to ease her conscience about what she would now need to do to him.

4

Philo hung up after listening to the overnight messages in the Blessid Trauma office. He patted himself down, made sure he had everything, his phone, his keys, his wallet, and the Sig Sauer 9mm handgun tucked into the crook of his back, inside the waist of his uniform pants.

“I don’t get it,” Grace said.

The fabric recliner inside the paneled office at the back of the garage had cigarette burns visible from across the room. Grace leaned back in it, her feet up, resting, adjusting her red-white-and-blue Philadelphia 76ers headscarf. For her, today would be a down day that she hadn’t put up a fight about with her doting husband Hank, something she needed after yesterday’s Amtrak suicide adventure. Hank would stay in the shop to babysit her. It was help he needed to give, Philo knew, as much as help she needed to receive.

Blessid Trauma Services occupied a two-story, four-storefront building in Philadelphia’s Germantown section, was originally home to a bar stool manufacturer. Lockers, shelving, storage tanks, chemicals, and biohazard equipment occupied the wall space surrounding the vehicles parked inside. The step van sat beside a Ford Econoline van, the Econoline black but unmarked for more discreet jobs. The third vehicle was Philo’s Jeep Wrangler. The business entrance was a glass door that opened onto busy Germantown Avenue.

“And what is it you don’t get, Grace?” Philo said, frustrated they were having this conversation again. He expected to be on the road with Patrick by 7:15 a.m. today, headed for a job in Port Richmond.

“One,” she said, “the fact you actually have a concealed carry permit, and two, that you’re packing today. And three, why the hell you won’t talk to me about it.”

She hadn’t noticed, but he was packing every day. “Fifteen years in the military, Grace. Stop looking for other reasons.”

“Yeah, Philo, but that was then, this is now.”

She watched the news, right? Radical Islamists, the Taliban, Daesh. Terrorism knew no space or time boundaries. For Philo, what was then, and half a world away, could easily be now, and right here. “Grace, please, not today.”

“Fine. Maybe I don’t even give a fuck. Maybe I’m even glad to see it, considering who you’re seeing today.”

On the message service last night had been a call from a Dr. Andelmo, deemed by Grace to be the Dr. Andelmo of recent organ trafficking infamy, alleged. The doctor’s call was pleasant, like follow-up calls people typically received from hospitals following their procedures, checking on a patient’s condition.

“Look, Grace, the EMT saw Patrick, remembered him from the ER, and this doctor heard about it. These people saved Patrick’s life. When he bolted he dropped off their radar. They’re curious about him, or maybe have some info on his identity.”

“That news got to the doctor awfully fast, Philo.”

“Traveled at what, the speed of the wireless airwaves, like every fucking phone call out there? Someone alerted the doctor and he called to check up on Patrick, that’s all it is. It’s what doctors and hospitals do.”

“Ulterior motives, if you ask me.”

“Whatever. We’re done here.”

Patrick poked his head into the office, already hazmatted head to toe in luminescent blue, carrying yellow gloves. Philo rubbed his sleep-deprived eyes at the bright colors, being tired a common condition for him. “Patrick and I will start that project in Port Richmond, then we’ll shoot down to see his doctor around noon. Let’s go, Patrick.”

Grace liberated the cigarette in her pocket, tucked it into a corner of her mouth, spoke out of the other corner. “He’s not his doctor, Philo! After this visit, Patrick needs to have nothing to do with him…”

An elderly man named Norman had called the cops. He hadn’t seen his friend, Phoenicia, at the Port Richmond senior center in weeks. The police had investigated, then called her niece in Detroit, the “person to call in case of emergency” from what they’d gleaned from Phoenicia’s purse. They then notified her friend Norman with the bad news: Phoenicia had been found deceased in her second-floor bathroom. The niece’s internet search subsequently directed her to Blessid Trauma Services; Philo provided a ballpark estimate over the phone. Blessid Trauma needed only a small deposit.

“You might consider using your home insurance to cover part of the remediation,” Philo had advised her.

“Why do you say that?” the niece had said.

“Just a hunch,” he’d said, not volunteering what a body decomp could do to a room, floor, whole house.

They parked at the deceased woman’s address, in front of a house nestled deep on a lot with silver chain link fencing boxing in its weedy property and a garage in back. The fence was utilitarian, the kind often used to contain a dog.

“Yes, my aunt has a dog,” the niece said when Philo called to say they’d arrived. “The police didn’t find him.”

The small, detached Arts and Crafts two-story might have at one time been considered charming. Its shingled exterior was now a washed-out gray, with chipped masonry steps that led to a red-brick front porch and outdated silver aluminum storm windows and doors. The front gutter had detached from the roofline and hung low, emptying into another crooked gutter hanging lower than the first, slanting farther down into a claw-footed porcelain bathtub in the side yard. Here was a life-size version of Mouse Trap, the 3-D board game.

The driveway led to the single-car garage at the rear of the property. Philo stopped the step van alongside the front porch. The smell, the one a person never forgot, entered the van’s interior through the vents. Patrick found the Tiger Balm and applied a liberal glob under his nose. He retrieved a portable caddy full of cleaning supplies from behind their seats and sat it on his lap, ready to receive his one-sentence pep talk.

Philo slathered his upper lip with the balm then bro-slapped his partner’s chest twice.

“No one better than you, big guy.”

“No one better than Patrick,” Patrick repeated.

They entered the yard through the gate near the bathtub. Icy brown water topped off the tub with a thick, glassy, dead-leaf crust. It was the third day that temperatures had dipped into the twenties. Liquids left outside in any receptacles, if not frozen solid already, would be soon. A north-south crack in the tub’s white porcelain hinted at its near-frozen contents, with dirty water drip-drip-dripping through the crevice and making a run for it along the thick, dark brown icicle that had already formed, connecting the tub to the ground. They stepped onto the porch, the floor’s wooden slats creaky, the path to the front door scuffed through the wood stain, exposing bare planks underneath. The house key left under a flowerpot let them inside.

Hot, stifling heat greeted them, the radiator pinging from somewhere under stacked cardboard boxes of Christmas tinsel near the front picture window. First order of business was to find the thermostat.

Phoenicia was apparently a hoarder. A surprise of sorts, only because the Detroit niece hadn’t mentioned it, but not uncommon with the elderly; maybe the niece didn’t know. Readying the entire place for re-habitation could take days, to clean out and neutralize whatever was growing in here. A few more steps inside the door, a careless Philo elbowed a picture frame to the floor, the glass shattering. He shook away the shards and picked up the frame.

“Sorry, ma’am.”

A photo of Phoenicia, Philo reckoned. Heavyset black woman dressed for church, fancy hat, bulky suit jacket over a pink blouse, dark skirt, a Bible in her hand, and a smile good enough for an AARP magazine cover. The worst thing for a crime scene cleaner was to see a photo of the deceased. It personalized the project.

Patrick

found the thermostat in a hallway. “Turn the heat down, sir?”

“Turn it off for the time being.”

“Okeydokey, sir.”

What was of interest, and the reason for them being there, was the house’s lone bathroom, upstairs. But surrounding them on the first floor was the homeowner’s detritus, evident throughout the living and dining rooms. Pigs and angels. Everything pig, everything angel. Pig salt and pepper shakers, pig and angel ceramics, pink piggy paperweights, bookends, statues, books about pigs, books about angels, angel costumes, angel wings, empty and full angel-hair pasta boxes, baseball cards for players named Angel, vinyl records and CDs by artists named Angel. And on two legs, a fiberglass pig-snouted butler, adult-size, in a tuxedo and holding a tray, ready for guests to rest their drinks. Sitting unrefrigerated on the kitchen counter were packages of—surprise—bacon, with squirming maggots. The porcine and angel memorabilia adorned the walls, floors, ledges, and furniture, and was also stuck to the ceiling by way of plastic characters tinted glow-in-the-dark green. Assaulting Philo and Patrick’s Tiger Balm noses was the mother of all odors, strongest near the stairs, coming from the second floor.

“I’m going up,” Philo said, adjusting his mask. “Join me when you’re ready.”

In bedrooms one, two, and three: if-pigs-could-fly wallpaper, pink stuffed pigs, collectible dolls in angel costumes, and on one unmade bed, pink piggy-themed sheets with food crumbs that supported a small ant colony. At the end of the hall was the bathroom, its eye-watering bouquet beckoning. He opened the bathroom door.

Whoa. Death and gravity in cahoots.

“Gravity, Tristan,” Philo’s elderly grandmother had once told him, gumming her way through the syllables, “is no longer my friend.”

True that, especially when seated on a toilet.

The cops had found Phoenicia, the forensics notes said, her bulk seated there, her top half wedged between the toilet tank and the wall, her body propped up until it began melting from decomposition. Her last known sighting had been two weeks and two days earlier, at the senior center. The coroner decided the date of her last visit to the center worked fine as the date of her death, and that she’d died from a coronary. In over two weeks of decomposition, gravity had done its thing.

Zero Island (Blessid Trauma Crime Scene Cleaners Book 2)

Zero Island (Blessid Trauma Crime Scene Cleaners Book 2) Scars on the Face of God

Scars on the Face of God Binge Killer

Binge Killer Hiding Among the Dead

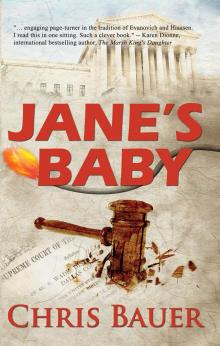

Hiding Among the Dead Jane's Baby

Jane's Baby